A 365-Day Project

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

January 21, 2008

January 21, 2008

Wow. The project has been over for three weeks, and I still haven't caught up with life enough to write. So I'll grind my way forward through the "We Are All Mozart" compositions -- I left off at the end of August! -- and perhaps say a few interesting things.

Housekeeping and statistics first. The project ended at 10:24 pm on New Year's Eve, when the last piece (Horizon (Ocean)) was finished. I had composed one hundred compositions on commission during 2007 for "We Are All Mozart," as well as eight not for the project, and one left unfinished (that was replaced by New Granite). Were the pieces played end-to-end, they would occupy about eleven hours. Given time for ten-minute intermissions every hour, that would make a concert that would begin at eleven in the morning and end at midnight. By the end of last year, I was exhausted ... and didn't even know how much. Not until another week had passed and some good nights of sleep were achieved did I realize the project had left me depleted of stamina and starved for sounds made by others -- but I still had to register all the titles with ASCAP and update my various catalogs. Why did I do this exactly?

But if you're starved for sounds made by me, here are some upcoming performances of WAAM pieces:

- February 20, De Rode Pomp, Ghent, Framing the Sum of Three, Michael Arnowitt, piano

- April 5, Roulette, New York, I lift my heavy heart, Beth Griffith, voice, with ensemble

- April (tentative), De Rode Pomp, Ghent, Scalar Rainbows, Leonard Duna, piano

- May 4, Flynn Center, Burlington, Vermont, Fanfare:Heat, Vermont Youth Orchestra.

There will be a collection of all the scores with a CD of the electronic pieces. I've mentioned this before, but since have got it priced at about $60 a copy. If you're interested, please contact me. There will also be a book early next winter, "We Are All Mozart: Inside the NonPop Revolution." More info upcoming during the summer.

* * *

Back where I left off, which was a then-upcoming performance of New Granite by the Vermont Contemporary Music Ensemble. Rehearsals were rough. Coordinating the live performance with the video of images was tricky, as there were no specific cues anywhere -- not in the images, which is a constantly slow stream, nor in the music, which is static and overlapping. With time short, I used a metronome. It was marginal -- being controlled by the metronome and yet trying to coordinate the performers and communicate expression was a challenge. By Friday night's premiere, it was still rough. I turned two pages at once and gave the wrong cues; we resynchronized, but the metronome was running slow and the images ended before the music. And at the reception, the majority of the comments were that the images were beautiful but the music didn't need them and they were in fact distracting. Another rehearsal was called for Saturday, and I pushed hard for intonation (tough to achieve at that low dynamic level) and a higher level of coordination. The performance was significantly better, but the audience still thought the images distracting. You can hear the performance of New Granite from that Saturday night. No images for you.

* * *

My WAAM compositions had been falling significantly behind schedule. A music engraving job of some fifty pages of difficult contemporary scoring had eaten into the time. The original plan for the project was to take the entire year off from 'day jobs' and concentrate on composing a piece each day. With far fewer pieces (and not even the prospect of one hundred by the end of July), the engraving, writing and editing work had to be done -- all of it, because alienating clients would not be a Good Thing. So five of the August pieces were finished in September, and all but one of September's got pushed to October. That one piece, finished on September 26, was Candied Sweet Potatoes, commissioned by David Mahler.

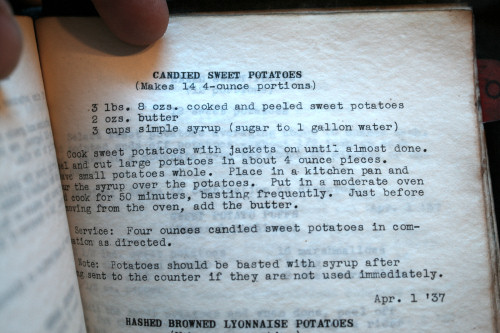

David is himself a composer, and one with a wonderful sense of humor, and a cook. He asked for a piece for three voices, and -- as I've mentioned before -- I went in hunt of a public-domain text ... and found one in the Child's restaurant cookbook, dated April 1, 1937. Recipes are gray areas of copyright, requiring "substantial literary expression in the form of an explanation or directions." Not much substantial here, and Child's (a Coney Island establishment well known to the older generation) was long closed. Safe! And funny in song! It was created in the manner of earlier music, but mixed and mangled through Mozartean and Renaissance progressions and cadences. You can read the score here and hear a fake-voice demo here.

A few days later it was time to write another chorale prelude for Carson Cooman. Years ago I studied with John Powell and Carlton Sprague Smith during the revival of early American music, and gained a deep appreciation of composers struggling with their own day jobs and inventing part singing as they imagined it. It was rough-hewn but moving, and among the most touching was written by horse breeder and teacher Justin Morgan on the death of his infant daughter Amanda. Here is how Morgan's original sounds in this recording made by the Roxbury Union Congregational Church under my direction in 1988. I had done an earlier set of variations that same year (for violin, two celli and harpsichord), and Carson's commission gave me a chance to rethink the music and its implications. The soprano in the RUCC recording had since died, and the music had more heft for me. Instead of a simple lament, it grew complex with announcements and reminders, so to speak. The music drew from Morgan, from my earlier variations, and from life's rhythmic pulsing. It builds, as with the earlier organ preludes of this project, from the unknown and hinted into the known original. There is a score to Loss of Innocence, and an mp3 demo.

Two related pieces came next, on the fourth and sixth of October. Patricia Goodson, the pianist who had commissioned two earlier pieces, wanted an organ piece for her brother. Another organ piece! This was to be a display piece, and as an example she gave the Widor organ toccata. As he was a very good organist capable of the Widor, I wanted to make this very showy, very tonal, and full of rhythmic trickery that only the player could assess. What came about was The Tides of Wales, with its fast but flowing fingerings and full-throated organ sound, based on the Welsh tune Ton-Y-Botel. Here is a score and a demo. It was a pleasure to write this, but it wasn't enough. I wanted more out of these ideas, and that came with a piece of precisely the opposite volume: a commission for two clavichords from Eric Somers.

I built a clavichord in the late 1960s (here is a partly obscured photo), and fell in love with its microscopic sound quality. It has two unique features. Because it contains just a single course of strings, a small soundboard, and tiny metal strikers (called "tangents"), the sound hardly fills a small room. It is a personal instrument suitable for the last moments of, say, Anne Boleyn in her boudoir. The other feature is how the sound is made. A string is hooked to the hitchpin rail at the back of the instrument, moves diagonally across to a bridge on the soundboard, and over to the tuning block. Felt is woven between the strings at the hitchpin rail and the tuning block. Plucking the strings achieves only a quiet thocking sound, as the strings are damped by the felt. Pressing a key raises the metal tangent, forming a small secondary bridge between the tangent and the soundboard's bridge (the other side of the tangent is damped by the felt), and producing a quiet ringing sound at the pitch created between tangent and bridge. The other unique feature is that the base of the keys is felted and flexible, so unlike any other acoustic keyboard instrument, the clavichord can produce vibrato by rocking the fingers on the keys. This effect (called "Bebung") is mysterious and very personal to the player.

The new two-clavichord piece was based on my just-finished Tides of Wales, but expanded and reconfigured for the limited range and dynamics of the clavichord, including specifying places for Bebung (which can be first heard about 25 seconds into the demo). There is also this score to Tangents, where the Bebung is marked with a slur and three dots (the only reference to which I could find was in a footnote to C.P.E. Bach's "Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments").

October was chock-a-block full of tonality. Lydia Busler-Blais teaches horn, and she wanted something for her students to reinforce their knowledge of bass clef. She wanted a piece with a holiday sense, but loathed most of the carols -- except the Coventry Carol. So it was to be another composition based on an earlier piece. It was certainly a temptation to write the horns high now & then, but I controlled those impulses and let them resonate in their round, low registers. Here is a score and here a demo to Lowing in Coventry.

* * *

The ongoing series for Seth Gordon -- twelve performance pieces for tenor guitar -- presented special challenges. It was too much of a temptation to grow cliché, to use old formulas. But with twelve pieces, those clichés would show up. Having already explored performance techniques, repetitions, and other structures, I decided to take the autumn as a time of oncoming dormancy and death. Musical staves were distorted and distended as visual variations on the music of the previous months; it was an illusion of the fall wind blowing the score pages, and the performer instructed to use each of the six elements of the summer months: "The distortion and direction shown in the staves should be transferred to the playing of the music, with each ending in a suspended state. The final suspension/improvisation is without any sense of ending until performed" with the next month's piece in the series. "The suspended state becomes an improvisation of failure and decay." Here is the score to Lunar Cascade in Serial Time: September.

One of the October pieces was composed on time, because it was a birthday present for Larry Polansky, composer, teacher, and player of any guitar-like instrument. Larry has a guitar collection, and the commission was to use several of his guitars in the course of the composition. And, of course, that meant to me "at the same time." Strapping on several guitars at once was dangerous, so I considered this scene: performer in the center, instrument facing inward toward the performer, all close, all the necks within reach. Larry could pick up a guitar and play it, and at the same time reach out (in a well coordinated manner, nicely choreographed without falling down) and pluck the open strings of the other instruments. And so In My Room was born. It also comes with instructions: "Instruments are placed on tables or stands where their open strings can be played. The ‘instrument in hand’ is picked up quickly and played (except in section V, where all the instruments remain parked), and returned quickly. The idea is to be as seamless as possible; when recorded, there should be almost no pause between the sections. The rhythms are specified to create a relaxed sense, and may be flexed so that the other instruments can be played without missing—in other words, the sounding note is important, even if it demands a little more time." The title was chosen because I'd not imagined this piece performed on stage, but rather personally with Larry in his room surrounded by guitars. Score and demo.

The commission month of September came to a close with Time's Arrow, written on October 24 for Anne Watson and commissioned by Bill Sallak. This clarinet solo is a high-energy blast. The score reads, "This piece is performed in a circle. Ideally, it should flow around the audience, but that is not usually practical in part owing to the need to memorize the music. Instead, it can be performed on stage with the performer moving in a semicircle, using several music stands (attractive and identical ones would be nice), beginning stage right, facing away from the audience and moving counter-clockwise toward the audience, circling around, and arriving in the back corner stage left, again facing away from the audience. The idea is to give a spaciousness to the sound as well as distract the audience from the performance details and toward the idea of sound in space. Or, it can be performed from one place. It’s entirely up to the performer. What do I know? Oh, and you can breathe wherever it makes sense, because no places has been left for it to be accomplished." It is relentless, almost eleven minutes -- score here and demo here.

By now I realized that there were nearly thirty pieces still to compose in 2007, and only sixty days to accomplish that schedule. Panic didn't quite set in, but it was coming. And just as it is said that one's imminent death increases one's focus enormously, so it was with the imminent end of "We Are All Mozart". All about that next time.

Child's Coney Island restaurant cookbook. If you want original pre-frozen-food era recipes, this is the book!.

Candied sweet potatoes recipe. Notice the date: My favorite yearly holiday.