A 365-Day Project

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

October 15, 2007

October 15, 2007

The true joy of this project arrives with the performances. The challenge was to write the compositions, and sometimes that gets in the way of appreciating that they actually will be performed.

A few weeks ago, a project coordinator called me to put some extra work in on a consulting job in digital audio. A New Media Expo was taking place in Ontario, California, and I had to be there and write a report of products and possibilities. Traveling eleven hours Friday and fifteen Sunday (Vermont is not exactly an air travel destination) didn't have much appeal until I learned that Saturday night, after the media expo, would be the premiere of Morning in Nodar, the double bass WAAM piece written for Tom Peters. I could go!

It's easy to forget that, although my own ensembles have performed my music since the late 1960s, it was only twenty years ago that very first performances came from other than my own ensemble. Sure, some of those personal performances were fantastic (like Plasm over ocean or Stoneworld Grey or Echo), but I bring forward the feeling of inadequacy through today of a career half-spent in oblivion. Creating a score like Morning in Nodar and believing anyone could perform it in less than a month was boggling.

Tom Peters could, and did. And this is no ordinary solo piece. It's in quarter tones. And it requires a bunch of bells tied to the bow. And the performer has to sing. Quarter tones. Hah.

No, seriously, for all its apparent clutter on the page, the music was intended to be very mysterious and sometimes still, and the idea was that the bells would ring as the bow reversed direction. I created a chart of measurements so that the bell strings wouldn't tangle and the bow wouldn't be weighted down. But it was too complicated to achieve in just four weeks, so Tom and I discussed other suggestions. Light sensors? Wii remotes? Elbow straps? Tom worked with the score and decided that the bells, though quite specific for each string, were random enough in striking that they could be grouped. He would work on it, he told me. The twenty years since my first 'external' performance had taught me to repeat one word as a mantra: trust.

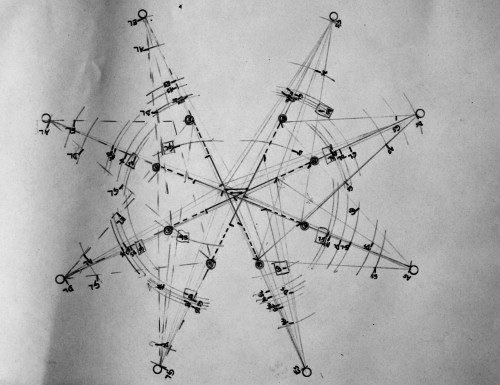

The original chart connecting bow to bells for Morning in Nodar. Tom had a better solution.

With trust came sushi. You just can't go from rural cows-and-pumpkins Vermont to California without having sushi first thing. Tom's father picked me up in Ontario and we drove to Pasadena, where Tom and Mary Lou Newmark were waiting. Mary Lou is now an old friend. David Gunn and I first met her as part of Kalvos & Damian, when she came from home in Los Angeles to the Ought-One Festival of NonPop, and followed up by performing her electric violin concerto with the Montpelier Chamber Orchestra two years later. Her latest project, Street Angel Diaries, originated with a Vermont artist who shook pictures of homeless people at her. We had a wonderful reunion, and then went for sushi. Delicious.

The performance was in the brand new Marjorie Branson Performance Space in the Boston Court Performing Arts Complex, the result of a gift from dot-com millionaire Z. Clark Branson. It's beautiful, comfortable, and with wonderful acoustics. And to my surprise and pleasure, my dear friend and now Corwin Chair at UCSB, Clarence Barlow, arrived for the performance along with his life partner, artist Birgit Pausmann. Tom's program included music by Eric Schwartz (Snakes and Ladders, a premiere), James Tenney (Beast, the brilliant 'beat' piece), Marshall Bialosky (Sauntering This Way), Robin Cox (the premiere of Terra Firma) and John Cage (Ryoanji, with Mary Lou on percussion).

Tom's solution to the bells problem was far more elegant than my clumsy measurement charts. Understanding the likely semi-randomness of the bells ringing when cords were attached to the bow, he strung the tuned bells in groups on four bungee cords attached to music stands at the top and to barn door hinges at the bottom. The hinges acted as foot pedals, and he could step on them to ring the bells as the bow reversed on different strings. Having to play (including left-handed plucking while bowing below the bridge) and sing (as I said, quarter tones), he also had to use his feet! When the performance came, it seemed perfectly natural, and his performance was equally elegant.

You can hear Tom's premiere of Morning in Nodar, and follow along in the score.

Tom Peters solved the bell problem in such an elegant way: bungee cords and barn hinges.

There's lots to catch up on with WAAM tunes from June, but that's all for tonight.

* * *

I promised the journal from our residency in Nodar. Here is the fifth installment. Please write to me if you want a copy of the full journal in PDF format with photos.

Sunday, April 15

I was up late, and Stevie was already out, and the others were working. After setting up the gear again, I headed into the village where Stevie appeared, strolling up the hill. We walked past the new small graveyard and across into the field, down through small tracks and toward the studios. From there I recorded the water coming into the town, a short soundwalk that briefly took in the water that supplied the village; we learned later from Luis that during the time when the town's population doubled (to sixty), the water was insufficient for hours at a time.

Lunch was the cheese from Seia, and some pasta, tomatoes and another cheese, bread, olives and wine, after which I went down the cobbled path to a pool where frogs and birds and insects could be heard along with trickling water on two sides. This afternoon we walked once more down into the village--again, this is no more than five hundred feet--to meet with some women with memories of early lullabyes and childhood songs. The first woman we're hoped to meet, (Maria) Donzília (DeSantos) Duarte, was away for a few hours, so we stepped over to the town square where a few families were gathered on a Sunday afternoon. The oldest woman, Laurinda Varzea, had a classic country face, full of crags and expressiveness and with a voice husky and melodious at once. She wasn't interested in songs of the past--only new things, she said, and strolled away. We met Laurentino Varzea and Hélio Gomes da Costa as well, participated in incomprehensible conversations punctuated by a familiar word or two, and then the two of us headed down to the dam, once a mill. We got lost on the terraces and ended up facing a small pasture with sheep and goats and a protective ram. We turned around.

By the time we reached the house, Donzília had returned and was ready to talk and sing; her voice was superb, rich and clear, and the songs she remembered detailed, some major, some modal. When she was done, Mário showed us his collection of doves and finches as well as rocks and antique farm items, and then invited us for a snack of his own ham and Donzília's sausage. It turned into dinner. We had bread and cheese and, of course, the wine. It turns out that this vinho verte is actually from American stock, probably the Concord grape, and has the purple color of grape juice with the smell of the grapes preceding the aroma of wine itself.

The Duarte's son Daniel was learning English, but too shy to speak. After much wine and chocolate-- their family is also in Switzerland-- we all walked back to the house, where I discovered that I should never let the recorder out of my hands. Putting it on the table, I had inadvertently hit the stop button, I think. Perhaps not, because the lights were still flashing. Whatever the case, the second recording of her singing was missing; fortunately, the video Cristina shot has all of it, albeit in monaural.

Tuesday Morning, April 17

The alarm was set earlier this morning to try to catch the goats and their bells for a full recording, but it wasn't early enough.

After another restless night--apparently this is really a cracked rib or two, and I'm following the pain pattern Stevie had back in 1993 when she was dumped from the horse--this morning is cool and bright. It was in the eighties yesterday, and dry. Smoke from another fire could be seen in the distance. After working in the morning on sound and images, we planned to go into Parada for some ibuprofen and sunblock. Stevie squeezed into the driver's seat from the passenger side--these small lanes mean we push the car right up against the wall--and as she backed up I saw the flat tire on the driver's side. Our peculiar fortune continues. We removed the tire (with a large screw protruding from the center of the tread), installed the mini-spare, and drove up to Parada's small pharmacy. The young woman at the Farmácia Costa spoke English well (she learned it from books, she told us, but rarely had a chance to speak it), and we bought the painkillers. Sunblock was another matter, and it was ordered. Parada received a delivery every day at about 6:15, so we would come back then, meeting the older pharmacist who had just arrived in his snappy white smock.

On the way back to Nodar, we encountered the postal van heading madly toward us, but in wellpracticed fashion, he skidded around us on the shoulder of the hairpin turn and continued his riotous pace up the hill. Mail delivery here is twice weekly. Back in Nodar, Luis promised to take care of the tire later in town. Lunch was ready by then, and we had chicken sausages, spinach and cheese, bread, and wine.

The repaired tire installation inspired a neighbor to visit, pointing out that he too owned a Nissan. His home is surrounded by gardens of roses and phlox and calla lilies as well as the ubiquitous grapes. We enjoyed a short conversation in increasingly familiar Portuguese (with ultimate recourse to hand gestures and snippets of French), and drove up to Parada, where the sunblock had not yet arrived. We continued out of Parada in the direction opposite our arrival (probably northwest; that's still not clear), curving gently into a valley with more terraces than we had yet seen, as well as a stone fairytale farm nestled against the hillside.

The road again began to rise, and rise, and rise, twisting upward through falling temperatures, eventually cutting across a mountain pass to the other side with a vast panorama of the valley. We were leaving the Department of Viseu, so took some photos and turned around. In Meã, we stopped at a small café and minimarcado, watching women all in black (as Tia dresses, as do all widows still in the region) with hoes and plants shuffling slowly down the hill after a day's work. Back in Parada, the pharmacist had the sunblock--but for fifteen euros. Stevie left it behind. In the meantime, Tia's sheep had lambed, and we hoped to see it soon. Not long after our return to Nodar, Gonçalo (of the ill-fated river hike) arrived to speak with Luis, convert some files, and work together on his four-year local products campaign. He was organizing farmers to encourage biologic (organic) production, and with government grants had developed materials to sell products by subscription--fifteen euros purchased a crate of produce weekly, monthly, or seasonally from a long list of local choices. The project was slow getting going, but looked to be a success. For most of dinner--chicken wings, mini-pizza, farmer's cheese, aubergine, bread and wine--we talked about the difficulty of independent farmers working together, and I brought up my experiences with the Vermont independent country stores.

After dinner, work continued. It is a fascination that here in a rural area where water comes down the hill, the power flickers in and out, and a mere thirty people live--with fewer and fewer, it seems, as the children leave; Daniel Duarte is the only child his age, and a taxi comes daily to pick him up for school several towns away--there could be one laptop computer per person in this house. There are seven of them running now as Stevie and Aaron work upstairs, and Luis, Gonçalo, Manuela, Cristina and I work downstairs. It is sometimes a very bizarre sensation to see all of our heads aimed screenward in a communal room where none other than natural sounds filter in the open doors.

Finding material for the birth song project has proven to be difficult, and we are in a state of adjusting the project here in Nodar. Fortunately, Gonçalo has brought with him a minidisc recording of very old women singing while baking bread. The original was in three parts, but there are only two of them left alive now to sing it--shiveringly beautiful in their quavering voices, with the simple harmonies major and modal at once, rising to a melodic seventh in the second part. We are each editing the recording for our own interests; I only wish that Gonçalo had been able to get the full names of the women. It had always bothered me that Gavin Bryars hadn't bothered to inquire when he wrote Jesus Love Never Failed Me Yet--the singer was merely a hobo to him, it seemed--and having only the first name of just one of the women seemed to continue that failure of attribution. I hope we can find all those names of the women in Candal, other than just 'Luisa'. Luis says we'll return next week to Candal to find them. The night grew late, with everyone else still working, but the back pain was beginning to press on me, so I went to bed.

This morning I awoke earlier than usual to tape the goat bells, walking down the cobbled paths to the fork where the goats usually clanged by in a leisurely line with the goatherd and his dogs--one of which Stevie had felt was very threatening the previous day as it was tearing apart the remains of a duck his family had given him. There was no motion at all for a half-hour (aside from the river, the birds, the insects and the gentle breeze, which is more than no motion but far less than a line of energetic goats), and then Stevie arrived; still no sign of the goats could be heard.

Somewhere on the paved road in the distance three goats were being led up toward a far field, and soon Tia was seen arriving with her sheep behind the studios. Then, not long after ten o'clock sounded from the town church, we could hear the sound of many distant goat bells blown our way on the wind ... but coming down the left fork of the paths. I had carefully placed my recorder on a stone, lodged in place so it wouldn't drop, and far enough off the path that the goats wouldn't likely eat it--but facing right.

The dogs would protect the sheep, so we couldn't get into the path now to make any adjustments. Compared to the zephyr wind, the bells rose to a clanging roar, with the farmer's voice and the protecting dogs. He put down a bucket of water and meat for the dog, who charged toward it, leaping over the stone and knocking down the recorder. It could not be fetched because the owner had left to get more goats--the dog would protect them from us--but fortunately it had landed with the microphone up and still at the same angle as before. Sated, the dog returned to the rock--to piss ... just missing the recorder. Another line of goats appeared with a second dog, and they merged at the fork, a jangling clutter of playing animals. The goatherd told us not to worry; the dogs wouldn't eat us.

They all moved away up the hill--turning left onto a straight path steeply up the side of the mountain-- so we retrieved the recorder and walked back home for a peek into the barn at the newborn lamb and its mother, then to a breakfast of coffee, bread and nutella, followed by a video interview with Luis to discuss the project so far, and how it had changed from its original premise. We worked out an idea for the final presentation that would include, in Stevie's words, "bread and birth," and in mine, "voice and song." As we see it now, this first step in the Birth Song project will result in a presentation video of dialog and song in English and Portuguese, with respective subtitles, and with still images and songs, as well as electroacoustic fragments, produced here in Nodar.