A 365-Day Project

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

January 24, 2007

January 24, 2007

It's much harder than I thought. No, not the writing itself, but the activity of writing.

Let me back up. When I began this project on January 1, it was certainly spotty. The 365 days had not been filled, leaving 280-some open. It meant keeping the panoply of day jobs, hunting for new work, and dealing with the process of mindset. If a day is full of small jobs -- a few pages of engraving, half of an article, some home improvements, an interview, some web work -- each of which can be swapped for another when the mind loses focus. But for We Are All Mozart, that swapping out (and the mind refreshment that comes with it) becomes impossible. There is one task for the day, one task only: to compose a piece of music to someone else's specifications. Maybe the specifications aren't tightly drawn, but they are present nonetheless, and they loom over the shoulder.

Another thing I hadn't counted on: coming face-to-face with my own style. In other words, enforced productivity is causing me to discover the common elements in my work, and I am at risk of being bored by my choices. Oh, no, this isn't something specific to me. It's why I'm bored by Mozart and Bach and Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky and Stockhausen. The common elements are as thick as summer grass, like sonic fractals. By exhausting them so quickly, it opens me up -- at this late stage in life -- to more choices that must be made.

Today I finished my tenth WAAM composition, and that offers an opportunity to reflect over the past three weeks.

* * *

But first, an aside about the annual Chamber Music America conference. I was there because my good friend Alex Shapiro encouraged me to go. I'm an awkward sort in public, and hardly as pretty as Alex. But I went.

It was what one might call a mitigated disaster. The setting, the posh Westin hotel in New York, was warm as New York always is -- and being in the New York orbit for the first nearly three decades of my life gave me a soft spot for gruff old Gotham. But CMA was chilly. There was no personal welcome to the event; indeed the head of the CMA spent three days looking the other way whenever she passed my table. Perhaps it was my heap of grey hair; I'd kept my Vermont look for the event, in stark contrast to the present New York fashion of shiny faces and close-cropped or shaved heads. With different clothing, I might have been holding a paper cup (though I'd likely get little more than a look at the inside of the psych ward for performing extended voice compositions on the streetcorner).

CMA isn't for poorly shod composers. I'd scraped together the budget for the conference and travel -- a thousand bucks, big money by Vermont standards -- booking an atrium table. Expecting the glimmer of lights and central beehivishness, instead I found myself as far out of the mainstream and still in the atrium as possible. In other words, my table was next to the toilets, where people walk with quick determination when they're going and look soiled (and away) when they're coming back. Oh, and there was no light. We had to ask for a light. The computerized directory was broken. Unpacked boxes were stacked next to me in the toilet hall. (An influential friend saw me and was furious over my placement; CMA lackeys showed up a few hours later promising better table accommodations next year. Hah.) It looked like a hobo's boxcar.

A computer show veteran from the Nineteen-Eighties, I expected my feet to hurt by day's end. They did. My two listening stations got a few visits. There was some composer commiseration; composer Edie Hill was opposite me on toilet row (next to a musicians' insurance company, which everyone avoided, taking them away from Edie's orbit), and none of the half-dozen composers was well-placed, the others in the far invisible corner of a side room. The publishers and agencies got the center of the room, giving air kisses and hand pumps all around. Moi, I sold one score. I handed out my tchotchkes ... business cards, "Concert Music. Buy Local." posters, narrated WAAM project 3-inch CDs, samples of scores, and some Cabot cheese packets with WAAM squares attached. (In my optimism, I'd brought along a data disk just in case I had to reprint my publicity material.)

The Cabot cheese packets in the crystal bowl weren't moving from my table, so I put the bowl in the reception area and kept a few nearby (with lime green WAAM sheets were taped to them in both locales). In reception they went much better, away from the weird hairy guy.

But the barrenness of the space was discouraging. I was located across from the Chiara String Quartet table, but they were only there a few hours, performing and workshopping the rest of the time -- very nice folks Chiara were, and first violinist Rebecca Fisher was brought up in Vermont. I was also next to the Synergy Brass Quintet, but they just had a table with posters and were performing at the jazz show in town. Their agent appeared after a day, and she was very enthusiastic about the group's performance of new music. The folks at the IMG agency table were hardly there at all. So it was me and three empty tables a lot of the time.

Beyond the logistics, the split between new and old was visceral. They were still arguing whether jazz was chamber music. I wanted to run away. Composers Reena Esmail, John Steinmetz, Pamela Marshall, Beth Anderson and publisher rep Judith Ilika stopped by, as did Joseph Franklin. That was a shock -- he's the guy who started Relâche years ago, and he was starting that new nonpop group during the year of our last Delaware Valley Festival of the Avant-Garde. He eventually moved to Albuquerque. Oh, and John Rockwell gave a pitiful keynote address.

Well, that's enough about that. Call it an opportunity for Stevie and me to visit friends -- Noah Creshevsky, David Sachs, John McGuire, Beth Griffith, Rob Voisey, Anne Fiero -- some of the most welcoming people in our lives.

* * *

Composition for the voice of Beth Griffith is a frightening honor. She is the musical combination a composer hopes for, with a staggeringly beautiful vocal instrument, a deep musical sense, powerful analysis of what she is singing, and a generous personality that one cannot betray. By Still Waters was written for Beth, and she was in the last performance of i cried in the sun aïda in 2006, where her questioning and musical demands opened up the composition in ways it never had been. And so on January 6 it was time to create her piece for voice, flute and guitar.

My immediate choice of text was Yeats's "The Folly of Being Comforted." I took it apart, found its music, and set to work -- and after two hours, realized I'd made a mistake. It was a terrible choice, and by noon I was still hunting. At last it came: Browning's "I lift my heavy heart" from the Sonnets from the Portuguese -- appropriate not only for its content, but for the fact that I'd recently learned of our acceptance to a residency at binaural media in Portugal.

It's often been noted here that the process of composition is quickly forgotten, sometimes as it is still in progress. So it is with I lift my heavy heart. The score itself is revealing; though the original was given to Beth, a scan of the manuscript's pages (1 2 3 4 5) and a comparison with the engraved score in progress reveal how my hand works.

The notation is idiomatic and idiosyncratic. Notes are grouped as needed. Barlines are for placekeeping, not timekeeping. The intimacy of a small ensemble and vocal cues dismiss the need for the formal structural elements of earlier music. Instructions of what to do and when to do it are given to encourage fluidity. Despite the notation, this is not an avant-garde composition; it is in the tradition of Browning, and the music is driven by the words. The result in Beth's hands will be thrilling.

Why Yeats or Browning, by the way? Quite simply, copyright. At least a dozen of my earlier compositions are not publishable and, because of my increased visibility, not even performable. Had I not been young and brash, I never would have set Cummings or Eliot or Prévert or Ginsburg. The Eliot estate doesn't give permission, period (or semicolon -- if you have a lot of money and promise a Broadway fortune, as with Cats, you can get permission). So when I need texts, it's from works created before 1923. A sad state of affairs, and you can read more about it on NewMusicBox.

* * *

Today, ten months after the fact, I learned that the brilliant organist and grand humanitarian Lucius Weathersby, who had premiered my Brand 9 from Outer Space and was teaching at Amherst after losing his life's work in New Orleans during hurricane Katrina, had died of a stroke. He was 37.

I was thinking of Lucius and recalling that after the intervening engraving work and CMA show, it was back to the WAAM project. Next up was a piece for trumpet and organ for Carson Cooman. It was another shift of perspective, working with organ, that monster of an instrument that was different in every location. Not only that, but Carson had asked for the piece to be written for a church trumpeter, that garden variety fine musician without pretensions.

The hardest part of composing for trumpet and organ is that it's all been done. So instead of fighting it, I let go of the struggle and created a simple opening fanfare, following by a single theme on which the entire composition was built. What was opaque became clear. Transforming linearly and vertically, the theme is shifted and adjusted, and eventually blended harmonically with the opening fanfare in a delicate trumpet pedal where its colors change as the harmony shifts underneath it. A tiny stretto makes a formal thematic restatement, and it returns to the theme, including a skeletal rework of the middle trumpet pedal.

Here is a score to coalescence and this is a (not so bad) Midi demo, albeit without the mutes.

* * *

In the twilight years of the avant-garde, it was possible to create performance pieces. But we've passed the twilight, and the globe has turned to a completely new day. So when Seth Gordon asked for a set of performance pieces for tenor guitar, I thought it would be easy to dip back into history and grab the good ol' avant-garde stylings, throw 'em into the Kitchen Aid, and come up with a dozen cheap compositions.

Here's the task that Seth put to me:

|

I'd like to commission 12 "short" pieces, one for each month, a single page each - the page could consist of written music, instructions, whatever floats your boat. Mix it up a bit. I put "short" in quotes because the works should be a bit malleable, particularly with the structure and rhythm - I'm thinking improvisation more along the lines of Cage's number pieces than, say, using the composition as a "head" for a jazz tune. At the performer's discretion they could speed it up, slow it down - the two areas which should be left (mostly) to the performer's discretion would be timing and dynamics, though there could be little pockets where something very specific occurs. The timing of each piece would be "from one to X minutes". The instrumentation would be for "tenor guitar, or other similarly tuned instrument(s), and existing sounds" - the tg is tuned CGDA, and the piece should be written with it in mind, though any similarly tuned instrument (tenor banjo, viola, mandocello, violincello) would be perfectly acceptable. By "existing sounds" the idea is that these pieces would not be meant to be recorded in a concert hall but in some area where there is a some amount of pre-existing "natural" noise - just where would be up to the performer. It could be on the street, in the woods, at a truck stop at 3AM, inside a cannery, in a shopping mall with muzak playing in the background... could be anywhere. The (s) at the end of instrument(s) is to imply that while the work is intended to work as a solo piece, any number of other instruments may perform it (or any of the other twelve works) simultaneously, as long as they all keep abreast of what the others are doing time-wise, and all end within a reasonable amount of time of each other (what's reasonable is up to them - the time frame would be agreed on by the performers beforehand). i.e., twelve musicians could get together and randomly hand out one "month" to each. Or, theoretically, they could all play the same "month" - because of the open timing, it would not be just a bunch of people playing in unison. There may be moments of unintentional unison (or the "Korean unison" Cage dug so much) - and extra little intstructions could be added at your discretion - like, say "if more than one performer is playing 'April', then they must meet at point X before both may move on to the rest of the score". |

What was I going to do with that? As with Carson's organ piece, it was more difficult than anticipated. The first task would be to come up with an effective structure. By midday there were pages of notes which might have been neatly typed up -- but in performance art tradition, I condensed them into instruction modules, arranged them along the borders of a sheet of paper, and designed it as part of the performance piece itself. The cover (which will be expanded with instructions directly to the performer, and later summarized in a set of performance notes) is here. It is an ongoing cycle of one, four, three, twelve, thirteen (day, seasons, months in seasons, months in year, lunar months in year), also including thirteen performance techniques.

Then came the decision of what to include. Because of the parameters of the set, photographs would be included, taken on the day of the composition. Each month's piece would be unique in its approach, and January's would be modular: self-contained modules of music to be repeated and intertwined among the performers. Importance would be suggested ("!") as would dynamics (">" "<") and order. The psychology would be derived from the photographs, and the single sheet could be circulated among performers in physical or electronic form. Here is the January score to Lunar Cascade in Serial Time.

* * *

There's more, but no time now. In the meantime, visit the calendar page and have a look at what's done so far, including In het Donkere Bos for viola and bass clarinet, Pivot: The House of Cloves for 4-track Midi, Moving to Lullaby for trombone solo, and Come, come for SATB chorus.

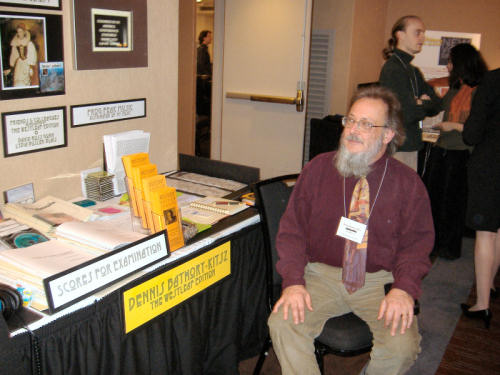

Dennis sits exhausted and table-shocked at the end of Chamber Music America's second day.