A 365-Day Project

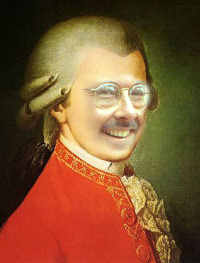

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

August 23, 2006

August 23, 2006

I try to keep promises, especially to an imaginary readership. So back when the confounding topic was Theodor Adorno, I promised to listen to some of Adorno's compositions. The recording arrived a few days ago ("Works for String Quartet" by Adorno and Hanns Eisler), and it's been playing repeatedly.

The step back in time into the sound of the Second Viennese School was a surprise. Having avoided listening to the era's music for so long, I found that it sounded fresh and -- after living in our own hyper-tonal era for a whole generation -- for a flickering moment understood why the atonalists had moved in that direction. Despite still being in the grip of romanticism, the Six Pieces for String Quartet sounded clean -- part of which can be attributed to the elegance of the treatment by the Leipzig String Quartet, part to Adorno's slight seventeen years, but mostly to the as-yet-unafraid approach to dismantling harmonic expectations. To be on the prenatal end of serialism is quite different from the bitterness of the subsequent fifty years. It is optimistic, hopeful, and even joyful in its discovery.

The string works on the recording fit right between the war and the Roaring Twenties with the German cabaret of Brecht and Weill, 1920 through 1925 respectively. The Six Pieces are a colorful set, the first (Sehr langsam, verträumt) halting and mysterious, and the second (Nicht zu langsam, doch schleppend in Ausdruck) full of Mahleresque fanciful heavy-footedness. The Schwer und dumpf third is a kind of overwrought passacaglia that never quite reaches past its initial ideas, and the fourth (Sehf hefting) again falls over itself in rhythmic repetition with nowhere to go. Adorno gets to stretch out again in the two final Langsam sections, and it seems that his slight ideas carry out more effectively when he doesn't rush himself, though the former section is overdrawn and already showing a soon-to-be commonplace structural cliché of a burst of energy before fading away. The latter is looking unashamedly backward to post-romanticism, dancing with tonality throughout and escaping the atonal skirmishes by concluding in octaves.

A year later, Adorno wrote a four-movement string quartet. The intervening year was spent well, and this quartet removes any suspicion that the future philosopher might have been a fraud as a musician. Indeed, this quartet from the 18-year-old artist suggests that continuing his work as a composer might have made interesting contributions to the repertoire and the thinking -- not so much because he at first adhered to the serial ideology, but because experience with its frustrations might have pushed him elsewhere. The Mäßig movement shows broader strokes albeit less color than the earlier studies, but the Sehr langsam is erratic, swinging between heavy-footedness (again) and strained elegance. The Äußerst rasch again owes more to Mahler than his Second Viennese colleagues with its parallel motions and expulsions of scale and arpeggio fragments out of silences. The last movement (Ruhig) opens and closes full of gentle trills, tremolandos, and modal melodies at octaves made with a modal feel, looking forward to Bartók's night music movements, but has an energetic and well-developed middle -- and is a confirmation of Adorno's seriousness and growing skill in compositional technique and musical ideas.

Unfortunately, by the Two Pieces for String Quartet, Adorno seems to have run out of those ideas, or at least the ability to sustain them beyond his initial concepts of five years earlier. Although these movements are the longest (seven and six minutes respectively), they are indecisive. The composer seems to want to run backward to romanticism, but instead plows forward into serialism haphazardly, full of gesture and what Thomson calls "wiggly counterpoint," but without being convinced of his choices. Just as the first movement (Bewegt) concludes, he seems to have clarified his direction -- but too late as he falls into the fade-down cliché once again. (I'm working without a score, so these comments are in part influenced by the heavy-breathing performers.) The second movement (Variationen) opens with a few measures of lush solo, instantly beaten down by instrumental responses. By now it feels he's working without a net. The variations are scattered and strain at the serial ropes, with gestures appearing and vanishing in a way that leaves a flattened texture and monochromatic background -- the serial sameness that afflicts weak work in the genre.

I wrote previously that Adorno was "out of touch with sound in particular and music in general." That clearly became the case as he increasingly moved into philosophy, and certainly his writing suggests it strongly as the rest of the musical world moved on. But nevertheless, Adorno's musical skill before he abandoned composition was credible, and whether or not his philosophical arguments were ultimately valid or helpful, my objections to his philosophical commentary as musically uninformed are withdrawn.

* * *

For those waiting for the long-anticipated composer survey on productivity, it looks like it will appear in either September or October's NewMusicBox. Frank Oteri is on his way to China, and the piece will either slide in before or after his trek. Bon voyage!

* * *

Often I speak about the small and personal character of Vermont. This morning I was in Lake Elmore, photographing the Elmore Store and interviewing its owners. A car pulled up and briefly waited as the full-on storefront photo was completed, and then out jumped Patrick Leahy, one of Vermont's U.S. Senators. On his way for a few days in Québec City, he stopped by the Elmore Store for a quick snack. And no security entourages or burly bodyguards were in sight. As the weather chills and careens toward winter, it's good to be reminded of the virtues of the Green Mountains.

Senator Patrick Leahy in the Elmore Store in Lake Elmore, Vermont, with store owner Warren Miller.