A 365-Day Project

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

July 24, 2006

July 24, 2006

In the ongoing quest to find sources, composers turn to found sounds, events, annoyances, and especially images. The subject of yesterday's commentary, images are rich in relationships of shape, heft, color and depth.

To readers who are not composers, the idea of needing to find sources may seem peculiar. Why not an ordinary harmonized melody? Though this may be entirely satisfactory, it doesn't necessary command interest day after day. And dipping into the personal well of existing ideas too often brings up a bucket of silt and stones. For example, one night I was dropping & lifting the bucket again and again without much luck while trying simultaneously to sleep and compose, and water dripping into a saucer in the sink kept me very awake. I teeth-grittingly fought the madness until it became evident that there was a background tendency in the dripping sound, a microtonal regularity of some kind. So the pattern was written down in the light filtering in from the window, analyzed as a Markov chain, and used for my (ultimately abandoned) Dripworks.

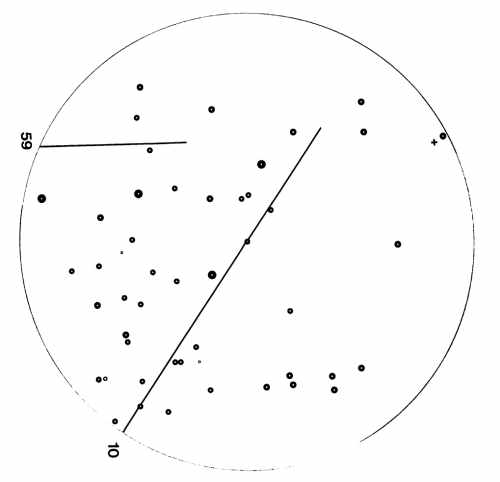

What other sources are possible? John Cage was fascinated by the stars, and when he died, the 1992 Vermont Composers Festival performed Aurora Cagealis as the final work on the program. It was based on star charts, shifted by hand, with the size and direction guiding the performers. The patterns are specific, the performance flexible.

Star charts form the basis of Aurora Cagealis, written in 1992 on the death of John Cage.

Images can be used for direct sound design. As usual when I try too hard, the search for source material for Quince & Fog Falls was going badly. The orchestration respected Essential Music's ensemble -- flute, piano, cello, and two percussionists -- but there was no clear signal on how to make it sound anything other than full of cliché. There is a heritage of character to new music groups that is both stark and rich, one that is also hard to resolve. It seems that mixed ensembles were propelled by Olivier Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time, wherein he succeeded by a single stroke in shaping clarinet, violin, cello and piano into a coherent whole. Sitting on the rocks gave me a shape because the landscape -- water, trees, rocks -- had a similar distinctiveness of texture and color, but a distinctiveness that also resolved into a coherent whole. Nature is complex but not discordant. Once this dichotomy resolved itself, out of those shapes and colors came the melody and textures of Quince. The contour of the rocks can even be heard in the shape of the passacaglia-esque cello melody.

The rocks, trees, and water shaped Quince & Fog Falls.

Quince was not fully abstracted from the shape of the rocks, but as images increasingly made their way into my music, discoveries about the movement within each image revealed how additional information could be extracted in more interesting ways than mere imitation. The task for Tirkíinistrá was huge: to create a set of 24 preludes based in some way on the landscape within the fifty feet between the back of the house and the far side of the brook, and tied together in a tonal/modal cycle. The landscape opened up immediately to the lens and each photo was unique in overall content, colors, focus, textures and directions. From each image were extracted patterns, some obvious, some obscured by the representational content. Computer software assisted in the extraction, and as if to reflect the colors and textures with the dynamics, a density chart was derived as well. The chart, placed along with each Prelude, guides the performer in dynamics and expression.

Source photograph for Tirkíinistrá Prelude #12. There are 24 Landscape Preludes in the composition.

Images can be especially rich because they contain colors and textures, with less of the calculated nature of a star chart, the representative shape of rocks and trees and water, or the direct transfer of image to expression. For Like to a Rose, the source material was extracted two dozen times from the same piece of rose quartz found behind the house in the Cox Brook -- not an image, but the quartz itself. The quartz had been sitting near the computer keyboard as useful thoughts of how to work on the piece for saxophone and percussion kept their distance. In a stroke it became as crystalline as the quartz itself that in its transparency were embedded three-dimensional patterns that could be followed through and across and down in any direction, and from these the melodic and rhythmic materials emerged for Like to a Rose.

This piece of quartz, from the brook behind the house, was the source of Like to a Rose.

Is this any way to find inspiration? Perhaps that's the wrong question. Inspiration follows the source, but inspiration is a weak tool -- the pick, not the wheel. Composition in free forms is driven by technique and inspiration, but can let down the listener with its even, consistent flow of ideas without boundaries, wide, omnipresent. With repeated listenings, one quickly finds the bottom of silt and stone. Within limitations or rules -- imposed or self-selected -- can be found a freedom not to choose. Whether writing a sonata or a sonnet, one can swim deeply below the surface of meaning, even deeper in a prelude miniature or a haiku, all tightly circumscribed. Then there is no choice, save to be overwhelmed, when the arroyo parches.

One may also listen for the non-musical. Voices are the most unintentionally wondrous sources. In 1980, for an article on software copyright, I interviewed a very young Bill Gates. That tape stayed in my packratty collection, unearthed a few years ago. It was very funny, entertaining if head-slapping listening, and shortly made its way onto Slashdot and Geeks in Space -- while I was listening to it for a different panoply of reasons. That whining voice (now so well known) became a sonic source, even a musical one, with different angles of length and depth. Syllables could be massaged into bells and scales, and developed into a library that was the stuff of wonderfully restful melody -- precisely the opposite of Gates himself, or perhaps a hint of the future Gentle Gates of great philanthropy. Soon it shaped itself into a lullaby, No Money (Lullaby for Bill), made entirely from that familiar voice.

Here's one for you. Create me something wonderful. (And tomorrow: Back to words.)