A 365-Day Project

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

July 22, 2006

July 22, 2006

"To whom it may concern."

These commentaries are addressed to myself, typing out loud. My exhortations and bullet points have "occasional colonialist elements," as a composer friend wrote yesterday from New York. In an exchange last year, a performer from Los Angeles referred to my writing as solipsism. I admit to them, even celebrate them.

There is a politics of writing in which we, within the code of authorship, are expected to suppress author-centrism and pretend (for it is pretense) that we can somehow obtain an objectivized out-of-body free pass from some cosmic viewpoint vending machine. By setting ourselves aside, we make room for others' views. Indeed, that is how the human mind and spirit grow if one assumes that there is no pre-formed inverse wraith sitting quietly in an interior room and waiting to be unlocked. My sophomoric understanding of Eastern philosophy suggests that there is a greater spirit of which we are a part, if we only are awake enough to find it.

Yet we don't truly set aside the ourselfness that has grown on the nutrition of others fed to us as parasitic neonates, but rather, once self-aware, we can but take on a cloak of otherness, the self remaining the point of reference out of which we gasp and suck. Yes, we are encouraged to "use the force" almost as a latter-day secular religion, but for good or ill we are not part of a Borg collective. Even in fiction, where the author disappears from the syntax, the author remains as master of the narrative, for despite André Breton's attempt to break down that self-centrism, it was still Breton's hand moving (no, I'm not a deus-ex-machina guy, especially the deus part). In biography, in history, even in science, the implicit "I" stubbornly remains in pseudo-objective passive-voice writing. One cannot read a biography of John Brown without being aware of what the author chose to omit. The presence of vibrant detail would require the cameras of time to be rolling and recording from infinite angles, and our understanding would have to be modulated by the entire historical and cultural Zeitgeist of 1830s America. We would have to live it, and engage in a forgetfulness that would preclude understanding.

What we can do is absorb ourselves mutually into, surround ourselves by, another's or others' actions and try to become them in some apparitional way. Improvisation functions with the observation, intuition, and action of interplay and the creation of incorporated apparition. At their best, teachers also lose their colonial urges, looking inside each person's work to find out where their paths are heading, guiding the search for blazes and spoor, and suggesting when to set up camp and eat and rest. These are all imagined into existence by "I" working as "we." And it is the transformation into the collective behavior of "we" as composers that has led nonpop to circumstances of obscurity with respect to the rejection of utility music.

Giving It Away

My correspondent asked whether the ownership of utility music had been given away or taken away.

It was given away, not taken away. The historical composer's role of joining in the celebratory, honorary, and ecclesiastical was let go of, even spurned -- a collective act that had ramifications for generations down the musicological road of the last century and into this one. Genres were discarded with the increase of composer-centric art music. For example, Vaughn Williams didn't give it away with his hymns, but who took his place? As a child, I watched the confusing collapse of Catholic music (what little there was to begin with) into saccharine guitar- or organ-accompanied monody. Where had Olivier Messiaen been? Meanwhile, Protestant congregations kept singing hymnbook-locked material, revised every half century or so to include only a token handful of new tunes. How about Benjamin Britten? Worship teams conquered the whole bible belt, with their country & western or rock 'n' roll approach. What little I know of other religious musics (most learned through recordings) suggests that a revival of pre-20th Century traditions has largely eclipsed new sacred composition. Where is Abraham Kaplan's renaissance? The nonpop composers were simply self-eradicated from the panoply of genres that they themselves had initiated and expanded into a mighty fortress of sound. No meaningful history of Western music can be told without integrating that story, and the same is true of music for celebratory events and everyday life.

Assuming a composer's interest is in being heard, then it's clear that the community of composers in their professional lives made staggering collective missteps that had nothing to do with musical styles or substance -- the usual strawlemmings leading us off the cliff of oblivion -- but were sociomusical in nature. The legacy of those missteps is twofold: Composers in 2006 have little opportunity to be heard at the same level as in 1906, and composers believe they need not be heard at that level (by adhering to the Babbitt line of thought). Their compositional solipsism-dogs are choking on their own tails. Why did they do that themselves, and to us, their compositional heirs? (Yes, that question is rhetorical.)

My arguments here are made with a belief that, just as we collectively made missteps throughout the last century, we can -- without compromise to artistic matters -- correct them in this century. And keep in mind the context in which I predicate my most annoyingly repetitive arguments, that of free-market capitalism. To use words like "value" or "worth" are part of that context. It's difficult to find a non-economic-based word when discussing inherent, um, uh, ahem, you know, ah, virtue. Well, that's not quite it, either. Not virtue -- significance. Relative significance. "Sign" isn't an economic concept. Okay, then. But, not to go too far astray, that capitalist model says "you get what you pay for" as if that phrase were engraved on Moses's tablets instead of "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's goods."

Though get-what-you-pay-for-ism is a lie of commerce, when running a small computer business, we were stunned to learn that not until raising the price of one of our products to more than double did people decide it was worth buying. Then we kept selling out of it. As one who believed in empowering people at lowest cost, I found that a very hard lesson in capitalist expectation. In such an environment, what is "free" worth? What do low commission fees suggest about the value of our trade? To ask it bluntly, what does it mean that an adept technical author can be paid $200 per hour but an adept nonpop composer accepts $200 per composition?

So we as nonpop composers can accept or reject the task of rebuilding our place in the culture (and this is no denial of the reality of many composers' lives, lives which are solitary by choice). The massive task is before us, as an examination of most mainstream nonpop ensemble programs makes evident. But we got ourselves into this state, the collective composer-we. No, it was not the music itself. It was the passive relinquishing of our role as artists meaningful to the culture, hand-in-hand with a conspiracy of other events.

The Colonialist Speaks

This colonialist now suggests solutions in the form of un-rhetorical questions: Why not consider writing utility music? Why not a birthday piece? Why not themes or transitions for a local radio program? How about an actual sacred piece? A graduation fanfare? Some five-second answering machine fanfares? Doorbells? Ringtones? A series of pieces that commemorate local historical anniversaries? We are surrounded by music that somebody is writing -- and that somebody rarely is a nonpop composer.

The only reason not to create utility music is to perceive no need for it or that it is lesser music, and such perceptions are the result of a century's worth of anti-utilitarian artistic propaganda that we wrote in our own hand.

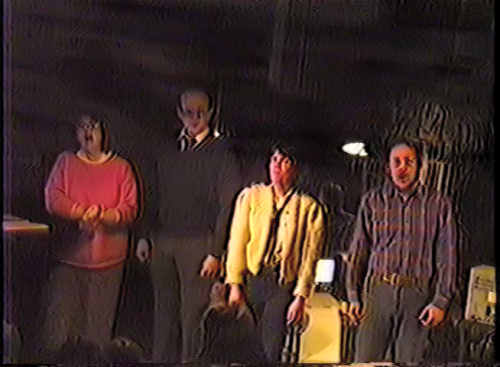

Any composer, if asked (or if the price was right, since I'm told everybody has one), would create a piece of utility music. Here is an example: Twenty years ago, when composer David Gunn and I were driving down the road after our two huge "Closing the Book on the Avant-Garde" concerts, we wondered what could possibly be next for our composition. It was winter, a tough patch for composers in general and pretty discouraging for us. Suddenly an absurd idea arose out of the conversation: cabaret. What kind of thing was that? So we challenged each other to write a show, and each of us did. Was it a betrayal of the nonpop credo? Who can say. Were they Great Music? Not likely. David wrote Big Sister, and here is the finale to my cabaret Beepers.

Final scene from Beepers, 1987. From left: Gayle Hanson as Erika, Stuart Duke as Ladiszlaw, Andrée Frazier as Reba, with me making a request appearance; off-camera, Deborah Chaffee on piano.