A 365-Day Project

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

July 2, 2006

July 2, 2006

Many composers have expressed concern about the "We Are All Mozart" project. The usual concerns are that it shouldn't be done (the "less is more" argument), that it can't be done well (the "quantity isn't quality" argument), or that it can't be done at all.

But the other day an interesting argument was made. To paraphrase: What happens if you can't get all the commissions? Almost no composer, after all, lives from commissions. So wouldn't failing to get the commissions be worse for nonpop? Wouldn't it automatically prove that a composer's time is worthless?

Ouch.

First, some reiteration. The 365-day project "We Are All Mozart" is not about me composing 365 pieces. It is about 365 pieces being valued enough to pay for. The terms of the project make no sense otherwise. The quantity is a talking point, an excitement generator. It could have been one piece a week (that's still 52, a lot more than most folks write, and two short of what I have right now), but 365 just sounds better. "Piece a day! Damn!"

Of course it's risky. But many composers have taken risks based on their ideas for nonpop's place in contemporary society. My belief in the impossible becoming possible arises from experience. In terms of my own past work, nobody believed we few nearly penniless artists could pull off three huge Delaware Valley Festivals of the Avant-Garde in the 1970s in the rusting old city of Trenton, New Jersey. But we did. In 1995, Kalvos & Damian was only a little show talking with local composers on Saturday afternoons at a 900-watt radio station in Vermont. Yet K&D has engendered changes with ripples -- albeit small ripples -- in new nonpop around the world. We were told that the Ought-One Festival of NonPop would fail in 2001, but it was a huge success. My personal opera project was never likely to get attention, but the story has run many times on Discovery and Travel channels. Few even believed Komposer Kombat was possible, but there were 41 creations born those two days. No one expected Rob Voisey's 60x60 Project to work, either, and now it runs around the world in multiple overlapping versions.

All these were personal dreams of encouraging the visibility of nonpop, not grant-supported New Music Industry undertakings. Beyond that, these projects have all been on our terms, and those terms were valid.

So "We Are All Mozart" has to be according to the simple terms of the project: It will demonstrate that composers are productive and flexible, and can respond daily and effectively to such demands, if they are compensated. It's intended to substantiate a fact that we know but the general public doesn't -- that we're not the elite, self-indulgent outliers of the free market system. That's its horizon of visibility for new nonpop.

How much is that challenge worth? Minimum wage in Vermont is $7.25/hour, my guideline for setting the fee at $1 per measure-part, $50 minimum. We start somewhere, and that was my choice. (Since I work twelve-plus hours a day, seven days a week, it won't actually generate that minimum, but it needs to be close.)

In other words, except at a very surface level this is not about the difficulty of the accomplishment, it's about perceived value of our work in a capitalist economy. 365 pieces don't mean anything if they are just little ditties some wanker feels like composing over a single malt. That's been done. Pure self-indulgence.

Yet, my correspondent argues, many composers quite simply like to, want to, or are driven to write music -- even Mozart. He emphasizes that if he is asked to compose a piece, he is honored.

The honor is true enough -- but not enough. It is the kind thinking that keeps us down and disrespected. Free honor becomes no honor. (And Mozart was paid, despite disliking the negotiations and reportedly being casual about spending.) In our society, everything is valued at the extreme in naked capitalistic terms (reject them if you will). I could certainly have more commissions if I said "Free music heah! Step raht up! Come & git it!" Or if I traded for performances, or pleaded for grant money so I could just write stuff, and roll it fee-free over to the performers.

But that's nonsense. There is no excuse that a product (and yes, a written or recorded piece is a product) that is actually used (as a composition is) be made for free, unless we do not value it ourselves, or consider our art to be a mere hobby. If we believe it has earned a place at the table of commerce (remember, we've created a product), then there needs to be a mechanism for paying for it. But there is no mechanism possible if the value is not made clear and evident to the public outside the realm of nonpop creation itself. Does the nonpop listening public really understand that composers essentially work for free within the capitalist system today? That many performers are recipients of welfare from composers? That even after commissions, composers are responsible for so much peripheral work (from copies through travel) that the net pay is reduced to the unsustainable? Why is art not, as many other cultures believe, simply part of civilization's infrastructure, always in need of repair and invention?

Okay, change of tone. Let's look at the numbers instead. How much musical value (and please pardon the hyper-capitalistic terms -- it's a structural thing for today) could be received at $50 for a solo piece of a few minutes' length? Or for a keyboard piece?

I am obsessed by numerical comparisons, no matter how specious they may appear at first. Overall, such comparisons may offer fuzzy but still helpful measures. This time they offer something quite crystalline.

Consider Chopin, whose Op. 28 Preludes run from average to darn good, and are now basic repertoire. At the "We Are All Mozart" rate, that would be:

- $50 each for Nos. 2, 7, 9, 10, 14, 18 and 20

- $52 each for Nos. 4, 6 and 10

- $66 each for Nos. 1 and 3

- $76 for No. 8, the "Raindrop"

- A paltry $150 for the incredible sonata-like No. 24.

The whole 1,050 or so measures of all twenty-five Op. 28 plus Op. 45 Preludes would be little more than a $2,000 purchase directly from Fred. Can you imagine? Two thousand dollars. (Heck, I'd pay $2,000 just to make sure they were never played again!)

Am I comparing myself to Chopin? Why not? My Tirkíinistrá: Twenty-Five Landscape Preludes for piano is every bit as interesting and aurally gratifying from a 21st century perspective. (And yes, it was done as a commission for performance, not payment.)

Here are some other famous bits of repertoire translated into "We Are All Mozart" fees:

- Telemann Trio Sonata in B-flat, four movements: $740

- Bach Cantata No. 4, sinfonia and eight verses: $2,222

- Beethoven Für Elise: $206

- Beethoven Pastorale Symphony, five movements: $22,663

- Beethoven String Quartet, Op. 131: $1,552

- Schoenberg Suite für Klavier, Op. 25, six movements: $502 (just the trio: $22).

- Stravinsky Rite of Spring: $54,500

- Cage Music of Changes, three sections: $180

- Varèse Density 21.5: $60

Although some are pretty handsome prices, even the blockbuster Rite will only buy you a 2006 Lexus LS430. If you get my drift. Put it another way. Folks spend more for dinner than the cost of a basic commission. It is simply dishonorable not to pay for music you will play, and honor increases with the fee.

Aside: Stravinsky reportedly agreed to be paid 1000 rubles for Rite of Spring. It took a little hunting to find that the 1910 five-ruble coin contained 0.1244 troy ounces of gold. At yesterday's closing price of $613 per troy ounce, those gold rubles would sell for about $15,250 present-day dollars. So "We Are All Mozart" comes up the winner on the Rite by about three-and-a-half times.

Second Aside: There's a parallel issue that's rotted up from the bottom of the new nonpop timeline. Why would performers not expect to pay out-of-pocket for new music? Are instruments, instrument repairs, venue rentals, concert recordings all more valuable and all grant-supported? A topic for another day.

At this point in my own career, I will no longer work for free except in special circumstances. I'm finishing older requests this year, the unpaid exchanges for performance. But the rest must be paid for, absolutely enough for subsistence and ultimately respect for the work being done. Sometimes excitement takes over, and performers receive a gift. When I finished Eventide in May, it was commissioned for only $250. But enthusiasm over the possibilities expanded, and the performers received eight movements for their two-and-a-half longs. Not so bad.

But back to an important question: What will happen if the project fails? Will it lower the value of composition? Will it prove that a composer's time is worthless?

Exactly so. And I'll have something very interesting to write about if it doesn't succeed. But the effort needs to be made. No cheating.

If you're still with me, let's try this from yet another perspective, with more numbers. What is a new small piece composed for a specific performer worth at fifty bucks? That dinner for two will just be flushed down the toilet the next morning, so it's at least worth that. How about hard goods? There are 49,300,000 Google hits for $49.95:

- Wireless keyboard at Staples

- Bouquet at 1-800-Flowers

- Bluetooth headset at Cell Phone Mall

- Clarity cordless phone

- Popeyez reading glasses at Amazon.com

- 3-pack of train DVDs at the Railroad Shop

- 1-oz. bottle of tattoo remover

- Dog warm shower hose kit

- Encyclopedia of Pinball, volume 1

- Dead Sea mud mask from TVProductsForLess

- Harrington's of Vermont turkey sampler

And so on. Any lasting value there? Think about it. An ounce of tattoo remover plus a 10-spot gets you Density 21.5.

All these comparisons are to make a point -- that not paying composers and even expecting not to pay composers is at heart unethical behavior. Okay. So if I can't get the 365 for the project, at least the discussion is now underway. And the very fact that the media (including the 'internal' media, save for New Music Box) won't touch the topic means it isn't about having too few commissions for a good story (at 50 commissions to date, that's already more than most people get) but rather speaks to the fear of talking about art and money and productivity and the whole panoply of forces that are pressed upon contemporary culture in place of the court and the church. (And you think capitalism is tough? Try the Emperor.)

(Many composers also fear talking about productivity, as my survey revealed. That's another story -- as soon as it's finished. Look for an announcement late next week or so.)

Ultimately, it's about changing the terms of the exchange. I am very hard-line about this project. Whatever happens, there will be something learned.

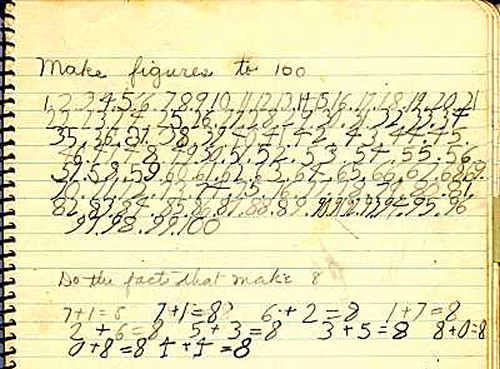

My obsession with simple numbers began early. Here is a page from my first grade book of number practice. Mrs. Bullock's School, Fanwood, New Jersey. She did not abide erasures, swatting knuckles.