A 365-Day Project

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

October 3, 2006

October 3, 2006

Notation. As composers, most of us use it to communicate our ideas. But it's a problem because notation, like words, changes over the years, as does its presentation. A perfectly legible musical part from 1200 or 1400 or 1600 is all but illegible for modern performers who aren't specialists.

The question comes up because a performer recently posted a complaint that composers use whole rests for empty measures in time signatures such as 5/4 and 6/4. Not a big deal, you say? He was in a microverbal rage. Okay, so some musicians have come to see the whole rest as equivalent to a whole note, but in practice it's a chameleon. It does serve to represent the silent equivalent of a hollow note without a stem, the whole note. And it also serves to indicate that a measure is empty. These kinds of ambiguities irritate composers and performers in different ways. (Composers and performers may take the next exit and have a glass of wine. See you tomorrow.)

There are two approaches that the publishers or copyists have to consider. The composer, like the writer, is concerned with the implications of the grammar and syntax. The performer, like the actor, is concerned with the sound and the presentation. Over the past two hundred years, they have grown somewhat apart. Take the case of accidentals -- sharps and flats. Historically, these came along as symbols to show the alteration of a melodic line; in a largely oral tradition that was being partly supplanted across the European continent by a burgeoning written repertoire, accidentals helped encourage the church effort to disseminate music in the Ninth century from its centralized base of power.

Nearly a millennium later, these symbols have come to carry multiple implications and identify several playing techniques. For some composers, these accidentals are merely ways of identifying a given note in the equal-tempered chromatic scale and taking care that its grammar shows its significance in the melodic and harmonic scheme. For others, accidentals are part of an advanced set of symbols that divides the scale into 19 or 23 or 43 parts with a more complicated, albeit seldom more advanced, grammar. For others, especially those working with flexible instruments unbound to keyboards, they represent pitch direction as well as the grammar, with sharps played higher than flats. And for those composers fully involved in grammatical authenticity, there is the compulsion to spell every note within the context of its use. Such scores are littered with grammatically proper notes (E-sharps and F-double-sharps and C-flats) which have enharmonic equivalents (F and G and B).

Today's performers -- again, unless they're stylistic specialists -- see something different from a composer in a musical part. They see instructions for performance, based on traditions that get the most music made in the least time. The notation itself is a means to a sonic end. I'm not saying anything remarkable here, except that it's not always the case. A few days ago, I mentioned that pianist Michael Arnowitt covered scores with analytical markings. He read the music not for just its sound, but also for its grammar and meaning. He wanted to understand not simply at the grossest level of communication -- what fingers to press down, when, and how hard -- but where he was going, the path to get there, and the environment along the way. I looked at a Beethoven sonata he had marked up. There was a chord penciled in where a rest was printed. "What's this?," I asked. He explained that it was the resolution of the previous chord, but clearly left out this time by the composer in a logical sequence. Why would Beethoven have done that? Its purpose clearly was to create and then violate the listener's sense of anticipation. In performance, he planned to put his fingers on the chord -- but not play it.

And take the conflict of composer and singer. It's all about the beams. For years, notes were disconnected at syllables with each pitch separately flagged, and then connected by both slurs and beams for melodic motion within a vowel. For the composer, that's not only redundant, it's syntactically wrong to break beams where the time signature and rhythmic sense create a connected group. For the performer, a reinforcement. For the composer, a decision: be redundant or spell correctly.

Traditions weigh heavily on composers and their engravers and publishers. Are silent measures written as staves with rests, or simply left entirely blank -- no lines at all -- on the page? Tradition says an altered note in a given measure is only marked once, but as music is more harmonically complicated, can the performer's mind retain that information with so much distraction? Maybe a courtesy accidental will be needed. How about the melody itself? During the Great Serialist Dominion, melodies could be so obscure and so jagged (and move from instrument to instrument) that the composers would bracket them with H¬ (Hauptstimme, the lead part) and N¬ (Nebenstimme, the secondary part). What a mess.

The grammar discussion doesn't even touch the messy verbal descriptions (what do andante or espressivo or con fuoco mean?), or the aspects performers consider merely to be guidelines (such as numerically indicated tempo). Composers have a grammar and syntax inherent to their music (whether of the particular composition, the composer's style, the era or the geography) that is as clear or ambiguous as a composer means it to be. But unlike the written word, the meaning-laden must then go through a process of modification and adjustment that may transform it from a musically meaningful line into no more than a performable line. Same music, different presentation.

In the past century, composers broke these notational rules out of necessity. Some returned to mnemonic methods of transmission, others to words alone. Graphics grew in significance, and many scores contained not a single traditional note. There were circles and spirals and modules and trajectories. The expanded musical vocabularly (chronicled in John Cage's collection of composers' scores in the book Notations and cataloged in Erhard Karkoschka's exhaustive book Notation in New Music) was sometimes obscure, but often a marvelously clear and even obvious replacement for the clumsy manipulation of notational methods based at best in the very proper and regular world of Eighteenth-century Mozart.

Notation progressed, in fact, like a giant ball of dust, picking up bits and pieces of visual usefulness as it rolled onward from the neumes of the first millennium to the serialists nine hundred years later. And then it bifurcated. The economics of publishing froze the notation methods somewhere at the end of the Nineteenth century as composers continued to adapt the symbols. And a consequent chasm began to open between performer and composer that had cavelike resonance (less than the stylistic and recording chasm, but nonetheless one with resonance) down through the next seventy-five years -- ending up in this Twenty-First century where a conductor rages over the meaning of a whole rest.

More tomorrow.

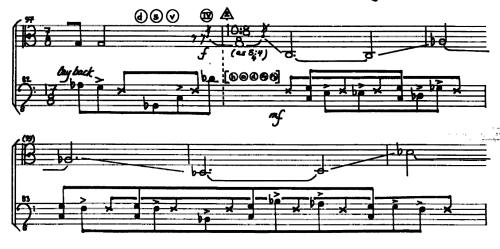

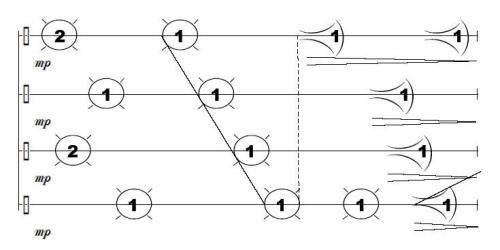

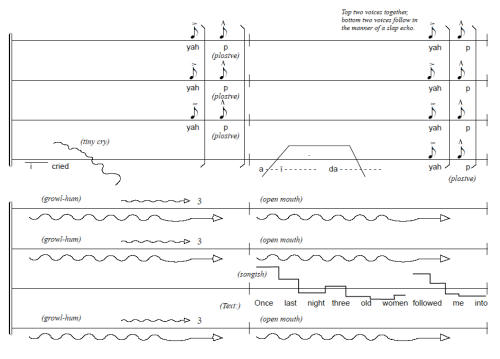

Three clips: Binky Plays Marbles, LowBirds (menu score), and i cried in the sun aïda. Each presents notational issues not found in previous times, which the performer might find discommodious. In Binky, a duet has separate, staggered time signatures and the double bass has three sets of alternating actions to play. In LowBirds, the performers have a menu score (shown) and individual menu parts whose contents are played within the symbols shown. And in aïda, the sound is described in words and graphical directions.