A 365-Day Project

"We Are All Mozart"

A project to create

new works and change

the perception of the

music of our time.

July 19, 2006

July 19, 2006

If you still care about Mozart by July, then read Alex Ross's latest hagiography in the New Yorker. In tearing down the mythology, he creates his own. His big conclusion: Mozart's Don Giovanni represents a transition to the Romantic era. Definitely another cup of coffee for me now...

Okay, that's out of my system.

For some time I've wondered about the extreme disaffection some nonpop acoustic composers have for electroacoustics. It goes both ways, yes, for many electroacoustic composers ignore the acoustic realm. But it seems more significant that a generation or more of acoustic composers who have grown up surrounded by electroacoustic music (where the converse is no longer true) choose to reject it. Is it simple choice, or élitist rejection? Lack of attention from academia, or selective ignorance? It's true that academia continues to put music in silos -- performance majors, theory, composition, acoustic here, electronic there, jazz there, studio techniques in another discipline entirely.

But it can't be that alone, and today's commentary isn't concerned so much with causality, but rather a kind of invitation to acoustic composers.

In my concern as a composer with public awareness, I date electroacoustics to its presence in Bernard Herrmann's accomplished score for the 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still. Together with excellent performances by Michael Rennie and in particular the matter-of-fact normalcy of Patricia Neal in what would otherwise have been a B film, Herrmann's ensemble that included two theremin soloists was a manifesto that electronic music had arrived. Although it's true that Switched-On Bach would make that impact in the classical realm, the marker year was 1951 -- which means every composer working today is part of the electroacoustic era. (A consequence of Day was, however, that electronic music would be stamped with the science-fiction genre, and all the implicit nichiness.)

The classical realm had by no means ignored electroacoustics -- its history is replete with compositions from the bird records played in Ottorino Respighi's Pines of Rome to Percy Grainger's Free Music to Olivier Messiaen's Turangalîla through Kaija Saariaho's Nymphéa. Yet classical music is also a great iceberg, impossible to add to, and crashing into and demolishing anything that would approach it. Despite its exquisite and irreplaceable use in, for example, Shostakovich's The Age of Gold, even the marvelously textured saxophone family has not achieved a place in the standard orchestra. And with electronic devices more likely to disappear than remain one family of instruments with circumscribed stability, the standard symphony orchestra has made no place for them.

(Because electroacoustic music depends on the diffusion of sound electronically, any classical recording is in truth electroacoustic. And even though one might consider that an artistic stretch, the preparation of the mind and ear for the delayed or selective or colored listening is a significant psychological and artistic shift.)

Among the reasons that electroacoustic music might be rejected by acoustic composers:

- Fixedness. Despite Messiaen or Herrmann's writing for live performances on the ondes martenot and theremin, electroacoustics truly came of age as an artform in the era of tape. Tape was fixed, and allowed only one interpretation. One cannot imagine Charles Wuorinen's Time's Encomium or Morton Subotnick's Silver Apples of the Moon from the pinnacle of the tape music era as anything but fixed compositions. Even the ostensibly changeable Earth's Magnetic Field by Charles Dodge is immutable forty years on.

- FX-edness. Outgrowing the notion that electroacoustic music is mere sound effects has been difficult. George Crumb's use of an electric string quartet in Black Angels was extraordinary but not prophetic. And for all its positive impact, Day seemed primary proof of the electronic music = sound effects equation.

- Insufficiency. The idea that electronics is a replacement for human musicians remains strong. Misguided predictions of the death of the studio or Broadway musician (some of which have actually come true) suggested that when electroacoustics 'grew up' it would serve only as a robotic substitute for a violin or trombone. Yes, emulation can work well as Jerry Gerber's music will show (or can even be heard in the relatively convincing electroacoustic demo of Yer Attention, Please for organ), but it misses the point of the electroacoustic art.

- Simplemindedness. Where it was once an arcane compositional field, electroacoustics has dropped in cost and expanded in possibilities to the point of commoditization. The range of beats and patterns and transformations in $100 software such as Audio Mulch is astounding, to the point that generic electroacoustic music created with such software is now called "photoshop music."

These complaints are relatively easy to dismiss: The era of requisite fixedness is over, sound effects have been done since Monteverdi first tremoloed tension in Il Combattimendo di Tancredi e Clorinda, emulation of acoustic instruments is of minor importance in the creative realm, and no one ever rejected a piano because it could be also used to play Heart and Soul. Also dismissable are complaints about unlistenability, audience hostility and noisiness, or that electroacoustics really just has refugees from 'real' classical music or orchestral ignominy. Everybody don't like something, and speaking of non-refugees, I've yet to hear Lowell Liebermann write a really catchy pop tune.

But not so easy to dismiss is the idea of expectations. Those who work in electroacoustics arrive either via the Stockhausen/Schaeffer/Columbia-Princeton stream or from the hiphop/Dr.Who/dance/Kraftwerk stream. The former suffers as badly from theoritis as the latter does from the curse of whateverness, and participants in both streams lob genre-bombs at each other. (Read all about them in Ishkur's Guide to Electronic Music.) The expectations on the dance floor and in the concert hall are as different as DMX, DJ Spooky, Aphex Twin and Jon Appleton. They don't mix well, and that might be the complaint of acoustic nonpop composers with electroacoustics.

This is the long way round to say that a psychological wall doesn't have to exist, and nonpop acousticians could grow significantly by learning and using electroacoustics -- and so could their audiences.

While acoustic composers deal mainly with pitches, rhythms, verticalities (harmony/counterpoint) and textures whose compositional interest arises from changing the relationships among them, electroacoustics provides both an expanded palette and an alternate acoustic reality. Just some of the expanded palette includes, for example, electronically originated sounds, transformations of acoustic and electronic sounds, placement and movement sound in space (spatialization and diffusion), sounds as themselves (sound objects), psychoacoustics, customized tunings, formulaic generation (beyond the canonical form), and formulaic transformation.

It sounds off-putting, but it isn't. Like that plaintive saxophone, the electronically generated sounds make a fine orchestral or chamber fit (as with the Messiaen, Saariaho and Gerber mentioned above) and are part of the everyday vocabulary of film scoring.

- Transformation of sound can be be heard as early as Stockhausen's Kontakte in the percussion-electronics transitions, but exist in orchestral scoring -- the dynamic crossing of winds, strings and brass in the Funeral March from Wagner's Götterdämmerung being the ideal example from the standard repertoire.

- Placement and movement of sound are also part of the standard repertoire, one startling experiment being the melody from the final movement of Tchaikovsky's Pathétique symphony, a melody which only exists in the interplay of first and second violins (placed across the stage in the composer's day). With electroacoustics, such placement and movement are not exceptional, and are part of the typical set of compositional tools; they can be ignored (as acoustic writing for, say, solo oboe contains largely one color).

- Sounds as themselves are more a 20th century development, explored by Anton Webern in acoustic music and in all manner of electronic music. 'As themselves' means that the sounds are compelling in a context largely unrelated to typical melodic or harmonic concerns. Advertising sound icons are helpful examples, even if they remain 'musicky' in content: the old NBC chimes icon, the Intel icon, the Philips icon, the walkie-talking ringtone, Windows or Mac startup icons, etc. (More thoughts on the small form.)

- Psychoacoustics are explored somewhat in acoustic music's orchestration (the perception of Stravinsky's octophonic chords as 'thuds' in Rite, for example, or the phantom words generated by the strings in Clarence Barlow's Orchidiae Ordinariae) but are widely employed in electroacoustics in the creation of auditory illusions, resulting tones (the ring modulator among the most well known -- an exquisite sound almost impossible to duplicate in acoustic music without extraordinary effort), and masking effects.

- Customized tunings are making a kind of comeback in both new nonpop and the presentation of pre-12TET (12-tone equal temperament) music (for a wonderful acoustic journey through tunings, listen to Ross Duffin's Temper, Temper). Whereas special tunings require re-tuning, multiple keyboards, and considerable finesse with the tuning hammer to perform such music, electroacoustics makes the entire range of historical and custom tunings quickly and easily available. This not only provides a means of exploration, but also increases the likelihood that non-12TET music will have greater hearing without being contorted to fit. (Composer Kyle Gann has a lot to say about this topic.)

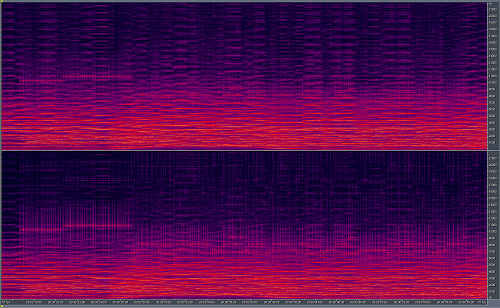

- Formulaic generation is one of electroacoustics' great strengths. Our Western heritage has a limited number of formula shapes, canons (singles, multiples, 'crabs' and enigmas among them), fugues and isorhythmic motets being the best known. (12-tone music was a rule set, not really a formula, though that is sometimes used accusatorially.) Formulas simple and complex can be turned into musical creations, including the fractals used in musical games such as Nick Didkovsky's MandelMusic or used to compose mysterious chamber orchestra poems such as my own Genial Music.

- Formulaic transformation is almost entirely outside the acoustic realm (one might think of retrograde tone rows as formulaic transformation). It is an area where acoustic composers might enjoy a rich learning experience. Among them are the ability to morph sounds one to another and filtering sounds to change their character or even extract 'hidden melodies' (the haunting background minor 'melody' in bellyloops and the lovely improvisational-sounding 'theme' in my FreeSimple both arise from stretching, smoothing and comb filtering just two seconds of voice). Another formulaic use is granular synthesis, audible in the watery scrunching sound during the tango played during the American Express "Blue" commercial.

Acoustic composers can learn these techniques with a small investment, and as a result enrich their acoustic work. (Unfortunately, a recent diversion has been software like Finale and Sibelius, which introduced audio demo creation using samples -- bypassing the entire learning process and replacing it with mechanical mouse-clicking.) Lifting acoustic music out of its traditional melody-harmony-rhythm framework can breathe new and different life into its future history.

A spectral view of an excerpt from Genial Music shows the patterns below its mysterious acoustic surface, patterns that arose from a fractal generation (click the image for a full-size look).